Bente Singko!

This is what I call a “no morals” story. No, not that kind of immorality, so apologies for getting your hopes up, just one of those meandering memories that somewhat reveal a “daily life” snapshot of how things used to be, not leading up to any dramatic “And the moral of the story is” moment. I got a few of these, and they’ve been coming back to me with a curious intensity since my return to the motherland. And like most of them, this one’s fairly short.

Like many Manila kids, our ancestral roots were really from other parts of the country, the “provinces.” Our family anchors were in the town of Polangui, in the province of Albay, Bicol, 453.9km or a 9h 47min drive south of Manila, according to Google (the Internet is cool!).

It was the very early 70s, I was only around 4 or 5, my sister a year younger, and like many other kids our age, we spent summers at Grandma’s house. For us, that was my maternal Lola Bicol’s house. Lola is grandmother, and Bicol is take a wild guess. Sometimes we all referred to her as Lola Polangui, although I have no idea why since my other grandmother was in Hong Kong at the time (guess what we called her), so there really wasn’t a risk of confusing her with any other lola, geographically-speaking. Especially since many of our other grand-aunts insisted we call them “Auntie” instead, but that may be for another story.

It was a nice, fairly big house, large grounds with lots of trees, many of them fruit trees. There were also a few animals about, like pissed off attacking packs of geese (believe me, you don’t know what terror is), pigs and chickens in the huge backyard, and two dogs, a brown dog named Brownie, and a black one named Blackie. She seemed to have those dogs for the longest time, until I realized later on, those really weren’t the same dogs I saw every summer over the years. She just kept getting a black dog and a brown dog and just never bothered to change the names. Now there’s a memory trick you’ve probably never heard about.

In front of the house was a main road, and the property had a tallish concrete wall in front. Well, high for 5-year-old me from the inside — I couldn’t touch the top of it without standing on a stool. But from the outside, adults could look over the top of it into the yard. I don’t really know how all that worked, now that I think about it, but read on and you’ll see why I remember that wall that way.

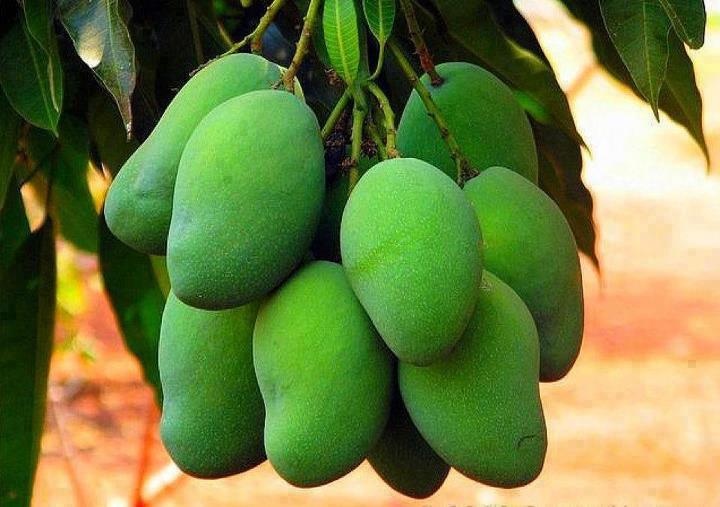

One morning, my lola held three green mangoes, I guess they were indian mangoes, from one of her trees. “Here’s something for you to do,” she said. “Take these and put them on top of the wall in front. You and Jessica, get some chairs and sit there.”

“Then what?” I asked.

“If anyone shows up and talks to you, just say bente singko.”

“Huh?” Now’s a good time to point out that the Philippines has “some 120 to 175 languages and dialects,” according to Wikipedia, and Polangui had one of them. Heck if I knew what anyone said every summer.

“Just say bente singko.” That’s 25, in case your Spanish sucks.

“But I won’t understand what they’re saying.”

“It doesn’t matter,” my lola said. “Whatever they say, just say bente singko.”

So that’s what my sister and I did. We took the mangoes and two little chairs to the front wall, and did as my grandmother instructed.

We didn’t really know what to expect, and it seemed to take forever before something did happen. Considering, however, that we must’ve had the attention span of a housefly, it couldn’t have been more than a few minutes, 15 tops, before a man’s head popped up over the wall, above the mangoes.

He said something. My sister and I stood on our chairs and stared up at him.

Me: “Bente singko.”

Him: More gobbledygook.

Me: “Bente singko.”

Him: Something something something something.

Me: “Bente singko.”

He started laughing. Then he handed me three 25 centavo coins. He took the mangoes and left.

We ran back to lola, chattering up a storm over what just happened and gave her the coins. She gave one coin to my sister. Another to me. “And this one,” she said, “is mine.” Then she turned and left.

So that’s my bente singko story. Or how I learned how folks sold stuff on their fences to passers-by in the old days, and how my grandmother managed to get us out of her hair for half an hour, while getting child slave labor and making a little profit. I wouldn’t be surprised if at the time those mangoes should’ve gone for less than bente singko each.

P.S. What I would give for a time machine so I can record that conversation.